My lifelong passion for ballet started over sixty years ago in a refugee camp in Esslingen, Germany. One of the very few memories I have of that period is my father picked marigolds for my crown of flowers which I wore when my dance group performed in front of our admiring parents.

But then, except for my early childhood dance classes, I was never encouraged to continue with ballet. For newly arrived immigrants to Montreal classes were expensive and babysitting was a far better occupation as far as my parents were concerned.

In fact, I was rather discouraged. In elementary school I was part of a handful of girls the ballet teacher referred to as KLUNKS. A very cruel, gay, middle-aged chap by the name of Mr McDougall was in charge. In our free after-school ballet classes we KLUNKS suffered in shame skulking in the back rows of the gym room while the petite, blond-haired, blue-eyed ballerinas flitted around gracefully to the Walz of the Roses. Yet, undeterred, I continued to search out ballet classes where ever they were held. One very cold winter day I remember trudging through the snow on my way to class. There was a bus strike that day and my journey was long. I slipped and fell on the ice and asked myself why. Why this intense resolve to dance. There was never an answer to that question. That’s just the way it was.

When I grew older, and even taller, I was fitted in with the boys during barre work. Madame Chiriaeff, the founder of Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, took an initial interest in me but dropped me when she realized I was seventeen. Had I been fourteen or fifteen she might have made something out of me, she thought. Too tall. Too old. Ah well…

Still I ran to classes in between lectures at McGill. And managed to pay for them.

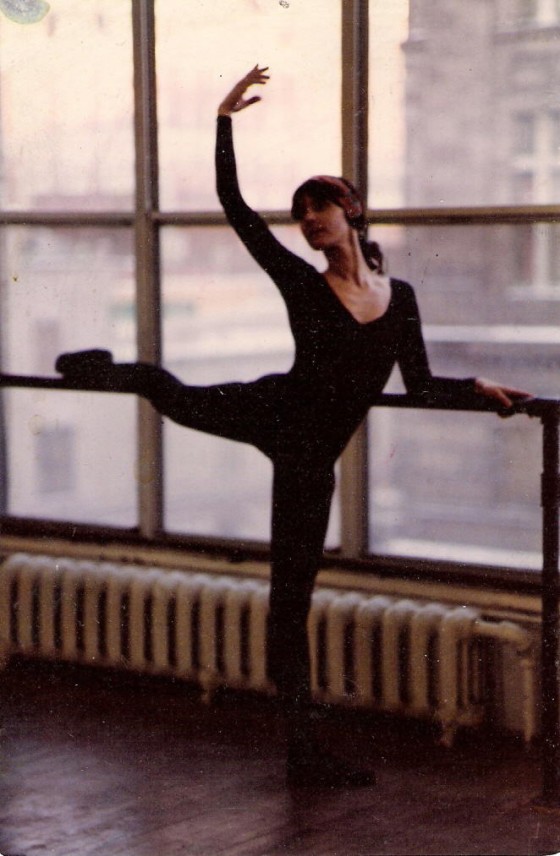

Years later, as an instructor at Concordia University I wore my leotards under my regular clothes to save time. My class ended at five. Ballet started at five. No late-comers. I remember abandoning my students at ten to five to dash madly up to St Catherine Street and Les Ballets Jazz. Up the slow-moving elevator, race to the dressing room, peel off my outer wear, and rush to the barre. There I developed a tremendous crush on our diminutive Ukrainian ballet master, Mr Litvinov even though he mocked my dropped elbows when performing the ‘porte de bras’.

To my distress my bolt from art class at Concordia was reported to the Head of the Department by a few disgruntled students. What a risk I was taking for my passion!

And then Latvia. I dreamed of finding a ancient ballerina from the Kirov or the Bolshoi giving classes in a spare room of her home just like in the delightful movie Turning Point. But I never did. “Ballet is for children,” I was told. “Not for you.”

For a time I did take over the gym in the Arts Academy to practice my ‘grand jetés’ but was soon ousted by the basketball team.

Now years later I’m still at it. Here in Ottawa my husband installed a ballet barre in the dining room. Sadly I’m struggling. But not giving up. How could I abandon my lifelong love? I can’t and I never will.