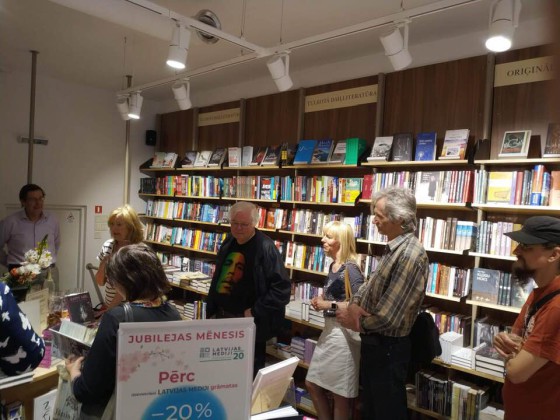

May 22 was a lovely warm evening in Riga. I was over the moon seeing all my Latvian friends and relatives congratulate me with wonderful bouquets. To my left is my husband, George Butlers, then it’s me saying a few words, across from me is Vivita Znotina, a relative from my husband’s side, then our own fb friend and journalist, Juris Kaza. Next, Egija Selga who figures in the book — a special loyal friend who saw me through many difficult moments in Riga. Then our good friend Egils Spuris who donated one of his images for the cover and finally Mikus Caverts who formatted the book in his own excellent fashion. My thanks to them all!

Chapter 1

I could never stand to be a tourist anywhere, and most especially not in Paris. My journey across the Atlantic was no summer vacation, no Junior Year Abroad. I was making a pilgrimage to the magical city I had loved forever, and where I’d live until the day I died—or that’s what I foolishly said to myself way back then.

In the fall of 1963 I had just turned twenty-one. I was a big, strong, energetic young woman, in love with everything about Paris. And the intensity of what I felt gradually found an echo, warmed Paris, coaxed it to open its fabled glorious arms and embrace my youthful adoration.

Slowly, very slowly, I began to feel at home and gradually I became part of the tribe. It took a while. Years, actually. Until I realized that to really fit in, to truly belong, I would have to marry the first Frenchman who asked me. (But that comes later.)

There were so many experiences, encounters, adventures. So much that I don’t know where to begin. And so it’s best to start at the beginning.

Growing up in French Canada (Montreal) I was however educated a l’anglaise. I went to McGill University when I was fifteen. I loved learning. The English classes (Shakespeare , Milton etc.. ) seemed dead and dull and I quickly gravitated to the French department. Classes were taught by native French professors. If you know anything about Canada you’ll know that there’s a vast difference between Continental French and Quebecois. The Quebecois I had heard all around me I found to be an ugly version of a wonderful language. Besides, the Quebecois people at that time were considered … well… white niggers, to steal a phrase from separatist Paul Vallieres. Les Negres Blancs de L’Amerique is the title of a book he wrote which caused a sensation – and an awakening.

I longed to get away from it all and connect with the birthplace of the wonderful literature I had enjoyed – Proust, Camus, Colette, St Exupery, Sartre, Simone de Bouvoir and a plethora of writings that had set me to thinking about … well… man’s fate. La Condition Humaine written by intellectual par excellence Andre Malraux caused a stir on both sides of the Atlantic.

I had a record collection: Jaques Brel, Charles Aznavour, Leo Ferre, Edit Piaf and many others. The Beatles? The Rolling Stones? Not my world.

It wasn’t only literature and music which made me into a Francophile. My mother and grandmother spoke French. Going to the French Lycee in Riga was the proper education for well-to-do Latvians until the Bolshevik occupation. My great aunt Berta had made regular pilgrimages to Paris for her seasonal wardrobes. Even my uncle had a French tutor. So how could I escape this family tradition?

In the fifties and sixties my family was struggling. Both parents were working. My brother and I had after-school jobs. There certainly was no money for frills like Junior Year Abroad. But I worked very hard. I waitressed and saved my tips. It was all for my grand adventure.

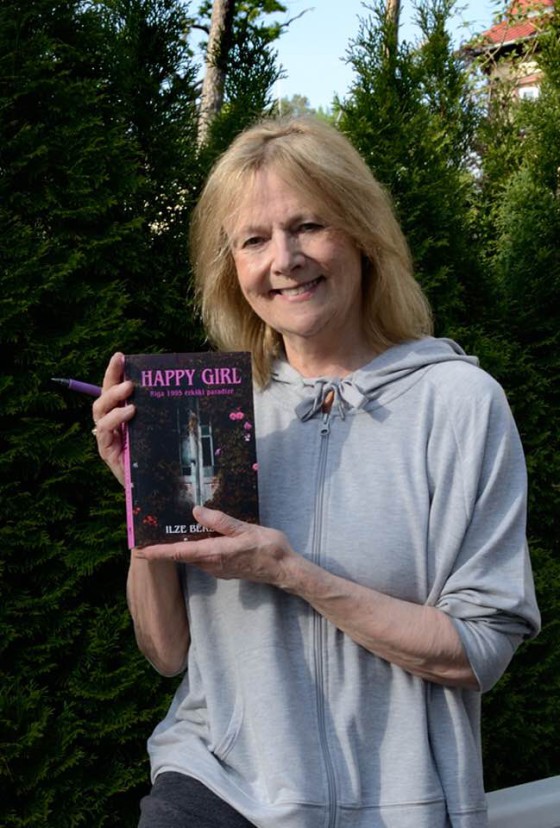

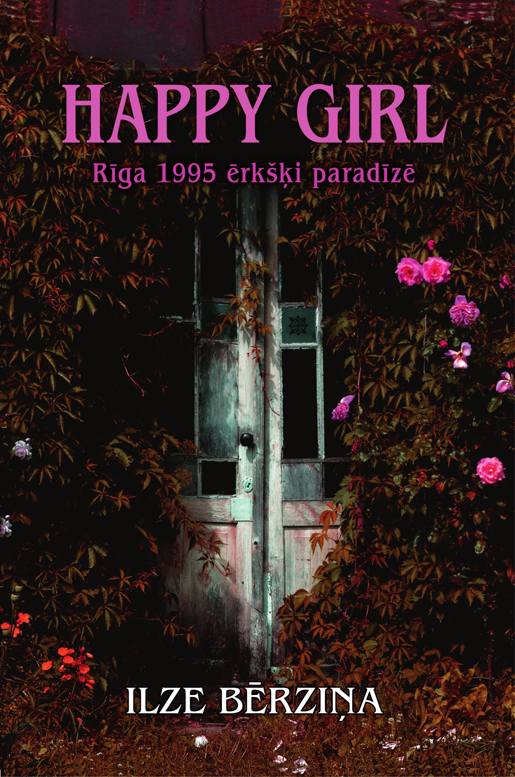

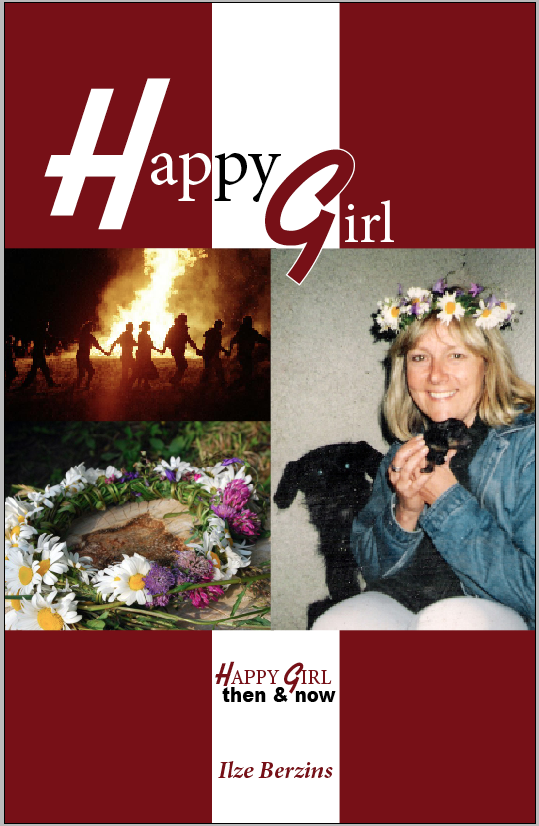

“God help you,” her father says, when Ilze Berzins leaves Canada for a new life in Latvia. But the Latvia she discovers in Happy Girl, a book first published in 1997, is rife with corruption, poverty, and decay. She encounters many shocks and disappointments, as well as spectacular beauty, fulfilling work, and lasting friendships.

“God help you,” her father says, when Ilze Berzins leaves Canada for a new life in Latvia. But the Latvia she discovers in Happy Girl, a book first published in 1997, is rife with corruption, poverty, and decay. She encounters many shocks and disappointments, as well as spectacular beauty, fulfilling work, and lasting friendships.

“The result of the author’s disillusion is a funny, lively, painful book,” wrote reviewer Diana Kiesners. “Berzins, along with a whole expatriate generation, was promised a fairytale Latvia that only needed independence to exist again. The promise is still unfulfilled.”

In 2012, Ilze Berzins travelled back to Latvia, visited her old haunts and attempted to recapture the giddy excitement she felt when she tried to settle there almost twenty years ago. This new edition of Happy Girl includes an account of this bittersweet homecoming. What she discovers will surprise, challenge and delight you. Will you agree with the reviewer of Happy Girl? Has the promise many “expats” took as a sure thing been fulfilled?

Read Ilze Berzins’ book and decide for yourself.

Chapter 1

They say you never know what’s around the next corner, and they are right. But back then, in the fall of 2005, I knew what was around the next corner. Nothing was around the next corner, or the next, or the one after that. Nothing else was ever going to happen to me. Nothing good, that is. Disasters would continue, though, dropped at my doorstep as if I had a lifetime subscription.

I had no way of knowing then that life was merely holding back, waiting to spring a mega surprise. Perhaps that was the plan. To creep up on me surreptitiously and hit me over the head when I least expected it.

Why couldn’t life have just announced itself, let me know that what I had so fervently wished for was indeed around the next corner? That is the mystery. I had to wait for that one momentous moment—that moment when the heavens aligned, and when those two ships that would have passed in the dark had come to a stop beside each other. And when a letter arrived.

That letter was left in my mother’s mailbox, which was attached to a very inconspicuous split-level bungalow on Emery Court in suburban Ottawa. Melodramatic as it sounds, I know for sure that, had the letter not arrived when it did, I’d soon have found myself six feet under or, at the very least, permanently off my rocker.

It was a bleak November morning which I remember as vividly as if it had been yesterday. I had a mountain of chores ahead of me and certainly no clue that anything special was coming. I would go on looking after my newly widowed ninety-three-year-old mother, and things would just continue as they had. I would get older. Then, soon enough, I would be alone.

Still, I did have a purpose in life. I had my writing, my dog and cat, the house, the garden, and the myriad little adventures that I shared with my mother.

As I did each morning, I cracked open the front door just enough to stretch out my hand and retrieve what the postman had delivered. At that moment I was conscious only of the cold wind, heard only my mother’s voice and realized that I should have put on a dressing gown. Closing the door I flipped through ads, some bills, then seized upon a few letters addressed to me that I hoped contained book orders. I had just put my most recent novel, Ghosts & Shadows, to bed and was waiting for my faithful readers, mostly elderly Latvian ladies, to request a copy.

“Anything interesting?” my mother called from her usual chair in her favourite corner of the living room.

“Oh, you know…” I replied dismissively. Since my father’s death in July, very little mail came addressed to my mother. My father had been the letter writer and assiduous card sender.

Clutching my letters (there were only two) I scurried upstairs to my writing room, which had been my father’s study. One letter was predictably Latvian Lady, the other was puzzling. It was the name of the sender that was peculiar. Not Latvian and not a lady. Perhaps a gent wishing to order the book as a gift? Yes, please, I said to myself, as I did every time a letter arrived. At this point my writing career was fast becoming a life jacket, and I eagerly welcomed any sign of interest to keep me afloat.

My father had been the muzhik of our family. Muzhik is Russian for a tough, single-minded man with conservative ideas who dominates his household. I survived this muzhik, yet I loved him too. My mother mourned him endlessly. After his death I moved into the family home because my mother needed looking after and did not want to be placed in a nursing home.

Since leaving their native Latvia in 1944, along with my two-week-old brother and two-year-old me, my parents had lived in dozens of homes, both as refugees in post-war Germany and as immigrants in Canada. In 1949 they settled in Montreal, and then retired to suburban Ottawa.

This house is where my story begins. At the time the suburb was called Nepean, but, some years later, Ottawa amalgamated and it became a part of Ottawa, while still remaining a burb.

A flat region of split-level bungalows and manicured lawns, it was great for conventional children and tired pensioners, but it was also a place so tight-assed that even cats had to be licensed, never mind dogs. Any dog larger than a toy poodle was considered a killing machine.

I was well aware that elsewhere in Canada, people living in Ottawa had a certain reputation. They have no souls was the consensus. When I lived in Nova Scotia, I wondered what these soulless people looked like. Were they like zombies or vampires out of horror movies?

Once I came to live in Ottawa I found them to be far less colourful than anything Frankenstein might have invented. Securely ensconced in their well-paid civil service jobs, bland, tight-lipped, cold-hearted, they were intolerant of anyone not exactly like themselves. In fact they were afraid of the unknown. Bedwetters, I came to call them, borrowing the word from American political commentator Ann Coulter.

Coulter came to Ottawa to give a talk to the local university but was warned beforehand by the rector to watch her language. Not one to be censored, she pocketed her ten grand speaker’s fee and never spoke—other than commenting, “Ottawa, the Indian name for The Land of Bedwetters.”

I was no Ann Coulter, and soon enough I became the unknown in this neighbourhood of Babbits, Stepford Wives, and Bedwetters. There were no friendly same-sex couples in those days. No blacks or visible ethnics. Only WASPS—my least favourite brand.

Life with my mother followed a pattern. We had our rituals and traditions. We had pets. Zola the tortoise shell cat, declawed but still so wild she’d kill baby rabbits and leave them for us as a treat. And then there was Clyde, my old shepherd mix.

Dinner in the summertime was grilled on a hibachi in the backyard. We both loved lamb and indulged. My father had had an aversion to lamb for some bizarre reason, as he had with many foods, so my mother had been deprived. Now she ate what she liked—lamb, spareribs, crab legs, smoked salmon, and even the great delicacy of her youth—caviar.

Drinks were important. We enjoyed a nice glass of Fat Bastard before dinner and then some more after. Later in the evening I was in the habit of taking Clyde for a walk through the neighbourhood. Okay, so he was off leash. So what? He was so old and so gentle that I hadn’t the heart to drag him along behind me. A lot of people in life just do what they want to. And nobody challenges them. But that wasn’t my case.

How was I to know that this simple stroll through darkened streets would soon land me face down, handcuffed, and in police custody?

Thanks to Juris Kaza for his photo called Sunny Riga. This reminded me so much of the time I lived on Čaka Iela that I decided to transcribe some passages from my book HAPPY GIRL.

1995

When I first arrived in Riga I stayed at the “korporacija” house called TALAVIJA.

But then my days at Talavia were drawing to a close. I had by now my puppy Happy, my cat Sweety, and all my stuff from Canada. The tiny room was crammed full –kitty litter and puppy and myself and bits of food. I had installed a hotplate on which I experimented with tough little pieces of meat but in no way could this be called home. I craved a kitchen and a wall to put up the few paintings that I had shipped to Latvia.

Egija, the caretaker’s wife at Talavia, started looking at ads in the paper and made phone calls. We both knew that my foreigner accent would have given me away and that any prospective landlord would ask three times the going rate. To my surprise many of the ads read: “For foreigners only.” Tthe hope was that these foreigners would eventually buy the apartment and the landlord would have cash and no landlord worries. Who but foreigners would have extra thousands of American dollars to purchase an apartment?

So here was Egija looking for a place for her “cousin.”

“Tikai ne bandita rajona,” cautioned Arnis, her husband. Well,it seemed to me that all neighbourhoods were bandit neighbourhoods. There were no foreigner enclaves. Embassy staff usually lived at the heavily guarded embassies.

Eventually Egija and I chose an ad to follow up on. An appointment was made with my prospective landlord, called Ivo.

Ivo sizes me up, ordinarily dressed as I was, and says:

“You’re a foreigner. Just look at you.”

Everything changed in a heartbeat and a new set of rules was established. Ivo will rent to me for one year at a reduced price. The deal is that I will renovate at my cost and then buy it at his cost. Ivo has in mind a metal door. He tells me how dangerous the place is. Well what place in Riga isn’t dangerous, I say to myself trying to look on the brighter side of the apartment issue. I could see Ivo’s greedy little mind working.

“She’ll renovate and then leave (all foreigners leave) and I’ll have a great apartment where I can live myself.”

“Okey-Dokey,” I assure Ivo.

I move in hauling everything up to the sixth floor. It’s late November.

Reality hits.

There is no water. Never mind hot water. There is NO WATER !

“Nu, ja,” Ivo says when I scream bloody murder.

“These are very old buildings. The pump was never intended to service twenty people per apartment (Soviets packed people in like sardines—one family per room).

“You can put in your own pump,” says Ivo.

“Right, Ivo. I’ll be supplying water for the whole house,” I say to myself.

“That’s the idea,” Ivo doesn’t say, but that’s what he means.

“Hot water?” I ask foolishly.

“Nu ja, it’s permanently turned off because there are debts.”

“But you can put in a boiler,” he adds.

Ivo is young. He has just inherited a building he can’t possibly maintain. Every young entrepreneur’s dream is that some fool foreigner who will make him rich. All the better that the fool be a woman. Easier to intimidate.

So Ivo thought before he met me.

I decided to stay in Ivo’s house until the Christmas holidays were over. There was some water late at night. I start getting up at two in the morning to fill the tub. Then in the morning I would boil a kettle and make a tiny bath in a pan of water. I lived like this in Paris, in my “chambre de bonne”, without squawking– but that was over thirty years ago. And then in Paris there were public baths where I could go to wash my hair once a week.

Towards the end of November the days got dramatically shorter. It was exciting for me. It was the first time that I had experienced this mystical night-shroud gradually moving in on everything and extinguishing the day. People lit candles in shops and at workplaces.

On the first Sunday of Advent, I lit the first candle on my Advent crown and put it in the window.

A month after I had moved in Ivo noticed that I had not yet installed a metal door nor had I put in a water pump nor had I bought a boiler.

This upset the young entrepreneur. He decided that I would be no good to him as a tenant and immediately embarked on terrorist tactics, with which I was already familiar. Unscrewing fuses no longer worked. Further fiddling also didn’t work because I had learned a thing or two about fuse boxes from Janis, my previous landlord.

Finally, one cold dark afternoon, I put my key in the lock. The key turned, but nothing happened. The door wouldn’t open.

To my horror I realized that the door has been nailed shut from the outside!

All my stuff was in there, including Sweety, my kitten. Luckily I had my dog Happy with me. Had I been inside, sleeping, they would have entombed me. No telephone, no fire escape. And no one ever paid attention to screams.

As fast as I could I ran to Talavia, to my friends Egija and Arnis. We telephoned my English students at Good Year Tire.

Within an hour, my brigade arrived: a van, three guys and a couple of crowbars.

Two hours later the door had been ripped open, all my stuff packed into the van and back we came to Talavia. Thank Goddess there was a vacant room.

So long Ivo! Have a nice life.

I was introduced as “Aunt Ilze” by Baiba, my new niece. We met at Frenchie’s Bar and Grill at Clearwater Beach in Florida where my husband and I had taken a brief vacation from the cruelest, most endless winter in decades. Aside from walking on the beach and playing tennis, meeting up with relatives was a must.

As I hobbled to my seat (I had dislocated my knee playing tennis and was wearing an ugly black brace) I was struck by the sheer glamour of my new niece. Bling at Frenchie’s where most were in tank tops and cut-off jeans! I couldn’t help but notice a huge diamond on her ring finger and a stunning tennis bracelet hugging her expensive watch.

The manager hustled around our table since Baiba and her husband had arrived by boat which was docked at Frenchie’s Marina. Baiba ordered seaweed and black coffee. I ordered rum runners and the best fish dish and then another rum runner, getting the vibe that Baiba’s husband was the host (not that we couldn’t afford it).

Of course I felt like an old scrag sitting next to the young (thirty-something) beauty. And Baiba was truly beautiful. Perfect teeth (veneers?), lovely honey-coloured skin, mesmerizing beautifully made-up eyes, subtly highlighted shoulder length hair.

Her husband was older (not much: ten years perhaps) but very nice. Her step son was polite and Baiba and hubby’s own little girl was shy and adorable. As we all got up to leave I couldn’t help noticing how very petite Baiba was. Like a doll.

Her husband and step son took the boat to their yacht club. We drove to the club in our rented car, Baiba giving directions.

Well—Tom Wolfe could have written about this club so much better than I, so I’ll just abbreviate. All white, (blacks served drinks around the pool) endless air kissing and fawning by the bikini clad ultra- toned friends to whom I was “Aunt Ilze” (in the knee brace). I was amazed by the manner in which Baiba navigated this ultra-casual, bikini clad and moneyed crowd. She knew what to say and the crowd liked the way she said it. They seemed to be enchanted by her tiny little body, her eagerness to please and her very slight European accent.

This is a success story. In her early twenties, Baiba escaped Purvciems and a dreary life in Latvia to travel to “Amerika.” She started out as an au pair (babysitter) ostensibly to learn English, but soon met a nice older man. And married him.

Baiba is a smart girl and I like her very much. She respects her husband and he, in turn, worships his pretty wife.

Just a note: Baiba works hard alongside her husband to be able to afford the Mercedes, the boat, the yacht club and their house.

It’s a win-win.